"Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us", the tune that eventually became associated with "John Brown's Body" and the "Battle Hymn of the Republic", with the familiar Glory, Glory Hallelujah refrain, was formed in the Southern camp meeting circuit, with both African-American and white worshipers, throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s,

In the first known version from early 1800, the text includes the verse

Oh! Brothers will you meet me (3×)

On Canaan's happy shore?

and chorus

There we'll shout and give Him glory (3×)

For glory is His own.

This developed into the familiar Glory, Glory, Hallelujah chorus by the 1850's. The tune and variants of these words spread across both the southern and northern United States.

NOT to be confused with "Glory, Glory Hallelujah" (or "Since I laid my Burden Down")

Folk hymns like "Say, Brothers Will You Meet Us" circulated and evolved chiefly through oral tradition rather than through print. In print, the camp meeting song can be traced back as early as 1806–1808, when it was published in camp meeting song collections in South Carolina, Virginia, and Massachusetts.

In May 1807, Stith Mead, a Methodist Episcopal minister, was one of the organizers of such a camp meeting in Boiling Spring, Virginia. The camp meeting inspired him to publish a collection of new and admired hymns, that he had heard there and at other camp meetings.

One month after the Boiling Spring camp meeting he published a new hymnbook in Richmond, Virginia titled: A General Selection of the Newest and Most Admired Hymns and Spiritual Songs Now in Use.

Among the songs in Mead's 1807 hymnal was Hymn 50, better known as the "Say Brothers" or "Oh Brothers" hymn.

I feel the work reviving (3x)

Reviving in my soul.

I′m on my way to Zion (3x)

The new Jerusalem

We'll shout and give Him glory (3x)

For glory is His own

Oh Christians will you meet me (3x)

On Canaan's happy shore

There we'll shout and give Him glory (3x)

For glory is His own

Oh Brothers will you meet me (3x)

On Canaan's happy shore

By the grace of God I'll meet you (3x)

On Canaan's happy shore

There we'll shout and give Him glory (3x)

For glory is His own

Oh Sisters will you meet me (3x)

On Canaan's happy shore

By the grace of God I'll meet you (3x)

On Canaan's happy shore

There we'll shout and give Him glory (3x)

For glory is His own

etc

Some sources say it appeared in Henry Ward Beecher's Plymouth Collection of Hymns in 1852 ??

I can't find any earlier publication of this collection of hymns than 1855. And even in that 1855 collection I can't find the song. SEE: Hymnal — Plymouth Church

In 1857 George W. Henry published a song collection titled: The Golden Harp, or, Camp-meeting Hymns, which contained the hymn "March Around Jerusalem", that could also be a variant of "Say Brothers, Will You meet Us?"

My Brother, Will You Meet Me

On That Delightful Shore ?

My Brother, Will You Meet Me

Where Parting is No more ?

Chorus

Then We''ll March Around Jerusalem,

We''ll March Around Jerusalem,

We''ll March Around Jerusalem,

When We Arrive At Home.

In 1858 words and the tune were published in The Union Harp and Revival Chorister, selected and arranged by Charles Dunbar, and published in Cincinnati. The book contains the words and music of a song "My Brother Will You Meet Me", with the music and the words of the "Glory Hallelujah" chorus; and the opening line Say my brother will you meet me.

Here's some scans from a revised edition from 1859

On November 27, 1858, "Say Brothers Will You Meet Us?" was copyrighted as a separate hymn by G.S. Scofield, New York, NY.

No copy of this separate publication has been located, but it was soon reproduced in the December 1858 issue of Our Monthly Casket, published by the Lee Avenue Sunday School, Brooklyn, vol. 1, no. 8, p. 152.

In 1859 this same version was published as song # 208 in Jeremiah Johnson's Your Singer's Friend or the Lee Avenue Collection of Hymns and Songs.

The words and music were also copyrighted on January 27, 1859, compiled in Devotional Melodies by A.S. Jenks (Philadelphia 1859)

Great songs sometimes seem to have a life of their own and survive by adapting to changing times and sensibilities. The song we now know as "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" has endured for more than 150 years and during that time underwent several dramatic changes in personality, as different writers and singers adapted it to meet their needs. As I said above the original version was a religious camp meeting song "Say, brothers, will you meet us? On Canaan’s happy shore?".

William Steffe is most mentioned in writing OR collecting this song in about 1856.

Whatever his private claims may have been,

Steffe was not publicly credited with the composition until November 3, 1883, when Major O.C. Bosbyshell published an article entitled "Origin of John Brown's Body" in the magazine Grand Army Scout and

Soldiers' Mail in Philadelphia. The piece was

picked up by Brander Matthews for use in his article "The Songs of the War", published in The Century Magazine (Volume 34, Issue 4, Aug 1887, p. 622).

In 1885, Richard J. Hinton, one of John Brown's biographers, wrote to Steffe asking about the circumstances of the writing of the original song. Steffe's four replies are contained in the archives of the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka.

On December 11th, 1885, Steffe wrote: "...though I never claimed any notoriety in music I want to prove by the best evidence the origin of the music of the popular song. Those who prompted me to write it are all 'gathered to their fathers' most of those who sang "Say Brothers will you meet us" -- are 'beyond the river'...." In his second and third letters, mailed more than a year later, Steffe stated that he sent a copy of the song to Hinton, but that since the copy was not received, it must have gotten lost in the mail. Steffe said he had trouble remembering the circumstances of the writing and was apparently in contact with others in Philadelphia who were present and could have testified that Steffe wrote the song. But Steffe never gave Hinton any verification from these other persons. In the last letter dated March 4, 1887, Steffe finally told the whole story of the writing of the song. He was asked to write it in 1855 or 56 for the Good Will Engine Company of Philadelphia. They used it as a song of welcome for the visiting Liberty Fire Company of Baltimore. The original verse for the song was "Say, Bummers, Will You Meet Us?" Someone else converted the "Say, Bummers" verse into the hymn "Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us." He thought he might be able to identify that person, but was never able to do so.

Steffe was born in 1830 in South Carolina. Moving to Philadelphia, PA, so he couldn't have written the "Glory Hallelujah" tune or the "Say, Brothers" text, both of which had been circulating for decades before his birth.

Steffe simply adapted the traditional camp meeting song and wrote a few new words. (SEE also further on in this story: WHO WROTE THE TUNE).

The song eventually spread to army posts, where its steady rhythm and catchy chorus made it a natural marching song.

Soon, though, a new version appeared that hitched the old tune to a more militant cause. When the abolitionist John Brown was executed in 1859, someone created a new, fiercer set of lyrics; the song now declared that

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave

and Glory Glory Hallelujah. His soul is marching on!

John Brown in 1859

Read all about the abolitionist John Brown ---> HERE.

By the time the Civil War began in 1861, the John Brown version of the song had spread throughout the Union army. Soldiers added new verses as they marched through the South, including one that promised to hang Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, from a tree. This version became known as the Fort Warren Version.

Soldiers in the Second Battalion, Boston Light Infantry, (a.k.a. the "Tiger" Battalion) were stationed at Fort Warren on George's Island in Boston's outer harbor at the beginning of the Civil War. Since the Fort had only recently been completed and there was still a lot of debris on the parade ground, they were set to work cleaning up. Two Maine recruits sang a simple song as they worked called "Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us".

Harry Hallgreen of the Tigers picked up the song and taught it to other members of his battalion. Among the Tigers was a certain Sergeant John Brown who came in for a lot of ribbing because he had the same name as the man who had been executed at Charlestown, Virginia, for trying to cause a slave revolt. Eventually Hallgreen invented a new line for the "Say, Brothers" song to spoof the lively activities of Sergeant Brown: John Brown's body lies a mouldering in the grave. Another member of the Tigers, James Greenleaf, added the tag line: His soul's marching on! More verses were added later.

Greenleaf was organist of a church in Charlestown and he had naturally much to do with the early arrangement of the notes of the song.

Mr C.S. Hall, an acquaintance of Mr Greenleaf often visited Fort Warren, and becoming interested in the song, he took hold with his friend to see what could be done with it.

Mr. C.B. Marsh also helped and the result was the composition of additional lines and the issue of the production as a penny ballad, on common printing paper, surrounded by a pretentious border.

It bore the imprint: Published at 256 Main Street, Charlestown, Massachusetts

Later, Mr Hall issued a more elaborate copy, giving both words and music, and headed it with a cut of the national bird.

It bore the words Origin, Fort Warren. and Music arranged by C.B. Marsh

At the bottom was the print as before, and a statement that it had been Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1861, by C.S. Hall in the Clerk's office in the District Court of Massachusetts

This Fort Warren song was the one Julia Ward Howe was referring to when she later wrote "Battle Hymn of the Republic", not the Methodist hymn

The origin of the John Brown Song is also told in detail in an article in The New England Magazine (vol 1 # 4 December 1889), written by George Kimball,

Here's the first recorded version of the John Brown's Body-version I could track down:

(o) J.W. Myers (1901) (as "John Brown's Body")

Recorded May 21, 1901 in Camden New Jersey

Released on Victor Monarch Record 3386

Listen here: Library at i78s

Or here:

On the same day J.W. Myers made a recording that was released on Victor A-824

Listen here: John_Browns_Body-JW_Myers.mp3

Here's a version J.W. Myers recorded almost 1 year later

The version that we know today ("Battle Hymn Of The Republic") came to be when an abolitionist author, Julia Ward Howe, overheard Union troops singing "John Brown’s Body" and was inspired to write a set of lyrics that dramatized the rightness of the Union cause. Within a year this new hymn was being sung by civilians in the North, Union troops on the march, and even prisoners of war held in Confederate jails.

Portrait of Julia Ward Howe, about 1865

As a result of their volunteer work with the Sanitary Commission, in November of 1861 Samuel and Julia Howe were invited to Washington by President Lincoln. The Howes visited a Union Army camp in Virginia across the Potomac. There, they heard the men singing the song which had been sung by both North and South, one in admiration of John Brown, one in celebration of his death: "John Brown's body lies a'mouldering in his grave."

A clergyman in the party, James Freeman Clarke, who knew of Julia's published poems, urged her to write a new song for the war effort to replace "John Brown's Body." She described the events later:

"I replied that I had often wished to do so.... In spite of the excitement of the day I went to bed and slept as usual, but awoke the next morning in the gray of the early dawn, and to my astonishment found that the wished-for lines were arranging themselves in my brain. I lay quite still until the last verse had completed itself in my thoughts, then hastily arose, saying to myself, I shall lose this if I don't write it down immediately. I searched for an old sheet of paper and an old stub of a pen which I had had the night before, and began to scrawl the lines almost without looking, as I learned to do by often scratching down verses in the darkened room when my little children were sleeping. Having completed this, I lay down again and fell asleep, but not before feeling that something of importance had happened to me."

The result was a poem, published first in February 1862 in the Atlantic Monthly, and called "Battle Hymn of the Republic".

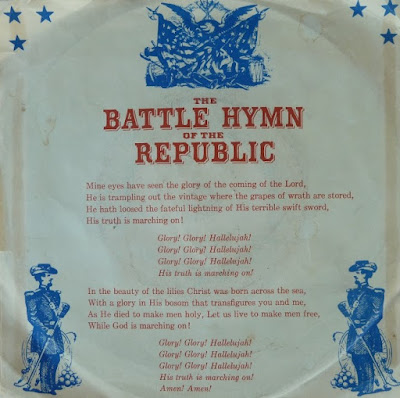

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

(Chorus)

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel:

"As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on."

(Chorus)

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat:

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

(Chorus)

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me:

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

(Chorus)

EXTRA VERSE:

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is Wisdom to the mighty, He is Succour to the brave,

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of Time His slave,

Our God is marching on.

(Chorus)

The poem was quickly put to the tune that had been used for "John Brown's Body" -- the original tune was written by a Southerner for religious revivals -- and became the best known Civil War song of the North.

And here's an original 1908 2-page article by the author C.A. Browne, entitled "The Story of the Battle Hymn of the Republic". This article details the history of the tune and that of the composer Julia Ward Howe.

Who Wrote The Tune?

In Book of World-Famous Music (5th ed, 2000), James J. Fuld has written an extensive and authoritative account of how the "Battle Hymn" and the "Glory Hallelujah" chorus evolved from the 1850s to the early 1860s.

Fuld writes:

"On Nov. 27, 1858, "Brothers Will You Meet Us?" was copyrighted as a separate hymn by G.S. Scofield, New York, NY. No copy of this separate publication has been located, but it was soon reproduced in the Dec. 1858 issue of Our Monthly Casket, published by the Lee Avenue Sunday School, Brooklyn, vol. 1, no. 8, p. 152. The music and words of the Glory Hallelujah Chorus are present. The opening words of the song are "Say, brothers, will you meet us," and the song became known as a Methodist hymn by this title. The hymn has been often credited to William Steffe but proof of his authorship is not conclusive.".

Boyd B. Stutler wrote a perceptive 1960 publication titled, Glory, Glory, Hallelujah! The Story of "John Brown's Body" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic". In it he shatters the myths of who wrote the "John Brown's Body" tune. Here are several excerpts:

"Most persistent in urging their claims were William Steffe of Philadelphia, Thomas Brigham Bishop of New York, and Frank E. Jerome of Russell, Kansas - but in each case their claim can easily be dismissed on examination of the records and proven facts.

The William Steffe myth is the one that has really muddied the waters, and he is the one who has profited the most - in name only - from his assertion that he composed the music of "John Brown's Body", later to be captured by "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". Anyway, Steffe has reaped a rich reward of unearned posthumous fame".

Then, if not William Steffe, who did write "John Brown's Body"? It remains a mystery.

Some researchers have maintained that the tune's roots go back to a "Negro folk song", an African-American wedding song from Georgia, or to a British sea shanty that originated as a Swedish drinking song.

The most likely guess would be it was written by a forgotten tunesmith and based on the Methodist hymn tune "Say Brothers". The "Glory, Hallelujah" chorus was used for "John Brown's Body" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic". This chorus must have been well known, since it was mentioned on the cover of the first printing of "Battle Hymn of the Republic".

The original sheet music cover is shown here:

BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC

Adapted to the favorite Melody "Glory, Hallelujah"

written by Mrs. Dr. S. G. [Julia Ward] Howe

for the ATLANTIC MONTHLY

Boston: Published by Oliver Ditson & Co.,

277 Washington St., 1862

What most writers have missed about this chorus is an important word was added in the original sheet music printing. In the second line of the Chorus there is an additional Glory making it sound even more stirring:

Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! GLORY! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

The first recorded version of the Battle Hymn of the Republic-version I could track down was part of an instrumental piccolo-medley

(o) Frank S. Mazziotta (1901-1902) (part of "Medley of American National Airs")

Recorded between 1901 and 1904 in New York.

Released on Columbia 504.

Although no artist is given on the label, Mazziotta is the one announced in the recording

Tim Brooks/Brian Rust associates two different artists with the recording sessions that include this master number: Frank S. Mazziotta and George Schweinfest

Listen here: cusb_col_504_01_t504_00.wav

In November 1905 2 vocal versions were recorded.

I'm not sure which one came first:

(c) Frank C. Stanley (1905) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Recorded November 17, 1905 in Philadelphia, PS

Released on Victor 4784

Listen here: cusb_victor_4784_01_b2893_03.wav

(c) George Alexander (1905) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Recorded November 1905 in New York

Released on Columbia A335

Listen here: Battle_Hymn_Of_The_Republic-George_Alexander.mp3

Howe’s lyrics have remained popular for over a century. However, people are still using the old melody to create new songs, some of which are sung at schools today. When you listen to—or even sing—this song, you might ask yourself what has made the tune so persistent, and so popular, over the decades.

A famous variant is "Solidarity Forever", a marching song for organized labor in the 20th century. Written by IWW bard Ralph Chaplin in 1915, while in West Virginia helping organize the Kanawha Valley coal strike. The song that would become the unofficial anthem of the country's labor movement by the 1930s.

First recorded by the Manhattan Chorus (and conducted by Elie Siegmeister) on the Timely Records label (Timely Records, created in 1935 by insurance salesman Leo Waldman, was the first company to specialize in protest / left-wing causes).

(c) Manhattan Chorus (1937) (as "Solidarity Forever")

Recorded April 29, 1937 in New York City

Released on Timely Records

Listen here:

In 1944 a sort of a supergroup consisting of Josh White, Burl Ives, Tom Glazer, Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry also recorded a version.

(c) The Union Boys (1944) (as "Solidarity Forever")

Recorded March 11, 1944 in New York City

Released on Stinson 622

Listen here:

"Solidarity Forever" was also one of the songs in the very first edition of People's Songs, a magazine to to create, promote, and distribute songs of labor and the American people.

(c) Pete Seeger, Tom Glazer, Hally Wood Faulk and Ronnie Gilbert (1947)

(as "Solidarity Forever")

Transcription of a soundtrack for a filmscript, prepared by People's Songs.

Recorded in 1947 in New York City

Listen to a sample here: https://rovimusic.rovicorp.com/playback.mp3

(c) Paul Robeson (1948) (as "Battle Hymn Of '48")

Recorded in 1948 during the Wallace-Taylor President Campaign

Released as a flexi-disc on the Record Guild of America label

Listen to a sample here: https://rovimusic.rovicorp.com/playback.mp3

All 4 above mentioned versions of "Solidarity Forever" were also contained on the wonderful Box: "Songs for Poiltical Action 1926-1953".

(c) Pete Seeger and Chorus (1955) (as "Solidarity Forever")

One of seven songs recorded in 1955 by Pete Seeger and a chorus dubbed "the Song Swappers" that included Erik Darling, later of The Weavers, and Mary Travers, later of Peter, Paul and Mary.

Together with the original 1941 "Talking Union" album by the Almanac Singers, this was released in 1955.

Listen here:

"The Battle Hymn of Cooperation", the anthem of the American consumers' cooperative movement, written in 1932, was also sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body"/"Battle Hymn of the Republic", but is likely influenced by the lyrics of "Solidarity Forever"

In 1959 the Mormon Tabernacle Choir had a million-seller when the 45 RPM record of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" was on the Billboard charts for 11 weeks and reached as high as No. 13.

It should be mentioned that for their 1959 version the Mormon Tabernacle Choir used a 1944 arrangement by Peter J. Wilhousky, except for a small change in the lyrics. In the 1944 Wilhousky arrangement, the last verse ends with the original words by Julia Ward Howe: "As He died to make men holy, Let us die to make men free".

This was changed in the 1959 Mormon Tabernacle Choir recording to: "As He died to make men holy, Let us live to make men free."

Here's a PDF of the 1944 Wilhousky arrangement: Scanned Document

(c) Mormon Tabernacle Choir (1959) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Listen here:

This is perhaps the first time when the word "Live" was replaced for "Die". Because it was such a hit, the change was adopted by other performers over the years.

At the 2nd annual Grammy Awards held on November 29, 1959, The Mormon Tabernacle Choir, directed by Richard Condie, received a Grammy

Award for Best Performance By a Vocal Group or Chorus.

(c) Odetta (1959) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Listen here:

The Blue Diamonds (the Dutch Everly Brothers) were in the army, when they recorded a version of "John Brown's Body" in 1962.

(c) The Blue Diamonds (1962) (as "John Bown's Body")

Listen here:

(c) Joan Baez (1963) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

(c) The Lords (1968) (as "John Brown's Body")

Nr 11 hit in the German charts

Listen here:

In 1968, Columbia released a 45-rpm record of two songs Andy Williams sang at the funeral of Robert F. Kennedy, a close friend: "Ave Maria" and "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". These were never released on a long-playing record.

(c) Andy Williams (1968) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Sung a capella with the St. Charles Borromeo Choir at the funeral of Robert Kennedy in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York on June 8, 1968.

(c) Johnny Cash (1969) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

From the Sept. 27, 1969 episode of The Johnny Cash Show, Cash is joined in the show-closer by the Statler Bros and the Carter Family.

Watch it here:

"Battle Hymn of the Republic" was also heard in the 1970 movie "Kelly's Heroes".

Watch it here:

(c) Leonard Cohen (1970) (as "Solidarty Forever")

Performed live on October 30, 1970 at the University of Wisconsin Field House in Madison.

Leonard Cohen performs at the Wisconsin Student Association sponsored, anti-war, "Bring them Home from Vietnam" Homecoming celebration

Listen here:

(c) Mickey Newbury (1971) (as "An American Trilogy")

In 1971 Mickey Newbury used "Battle Hymn of the Republic" to write a song, which was in fact a medley of three 19th century songs: "Dixie", a blackface minstrel song that became the unofficial anthem of the Confederacy since the Civil War; "All My Trials", originally a Bahamian lullaby, but closely related to African-American spirituals, and well-known through folk music revivalists; and "Battle Hymn of the Republic", the marching song of the U.S. North during the Civil War.

He called his medley "An American Trilogy" and had a big hit with it in the US.

Listen here:

(c) Elvis Presley (1972) (as "An American Trilogy")

Recorded live in Las Vegas on February 17, 1972.

Listen here:

"Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley" is a 1971 spoken word recording with vocals by Terry Nelson and music by pick-up group C-Company.

The song is set to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". It offers a heroic (???) description of Lieutenant William Calley, who in March 1971 was convicted of murdering Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai Massacre of March 16, 1968.

The song was written in April 1970 by Julian Wilson and James M. Smith of Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

Originally in January 1971 a few copies of it were issued on Quickit Records.

In March 1971 Shelby Singleton, publisher of "Harper Valley PTA," obtained the rights to the song and issued the recording for national distribution on his Plantation Records label. The single sold over one million copies in just four days, and was certified gold by the RIAA on 15 April 1971. It went on to sell nearly two million copies, and got a lot of C&W (or REDNECK) airplay.

Listen here:

But there were also songs that blamed the massacre of women and children on the politicians for sending US soldiers to a war which "we could never win".

(c) Beach Boys (1974) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Mike Love on lead vocals.

Recorded on November 5, 1974, during the Caribou sessions

It was never officially released.

Listen here:

(c) Whitney Houston (1991) (as "Battle Hymn of the Republic")

Whitney sang it at her concert to the troops called "Welcome Home Heroes".

Watch it here:

(c) Van Morrison (1999) (as "John Brown's Body")

In 1979 Van Morrison recorded a version of "John Brown's Body" during the "Into The Music" sessions.

As an outtake, it was intended to be released on "The Philosopher's Stone"

The Philosopher's Stone Volume One was originally scheduled to be released in July 1996. When it was released, some of the tracks had been changed; "When I Deliver", "John Brown's Body" and "I'm Ready" were replaced by "The Street Only Knew Your Name", "Western Plain" and "Joyous Sound".

"John Brown's Body" and "I'm Ready" were eventually released as B-sides on Morrison's 1999 single "Back on Top".

Listen here:

The 1994 FIFA World Cup theme, "Gloryland", used parts of the "Battle Hymn" that reached an international audience in celebration of the 1994 soccer world championship.

(c) Daryl Hall and Sounds of Blackness (1994) (as "Gloryland")

Listen here:

"Little Peter Rabbit" is a children's Nursery Rhyme set to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic".

The words are:

Little Peter Rabbit had a fly upon his nose,

Little Peter Rabbit had a fly upon his nose,

Little Peter Rabbit had a fly upon his nose,

And he flipped it and he flapped it and the fly flew away.

Powder puffs and curly whiskers,

Powder puffs and curly whiskers,

Powder puffs and curly whiskers,

And he flipped it and he flapped it and the fly flew away.

Some sing

Little Peter Rabbit had a fly upon his ears,

And

Floppy Ears in place of Powder Puffs.

The lyrics are inspired by the children's book "The Tale of Peter Rabbit", a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter in 1902, that follows mischievous and disobedient young Peter Rabbit as he gets into, and is chased around, the garden of Mr. McGregor.

"Little Peter Rabbit" was probably first published in 1957 as song # A-27 in Children's Hymnal.

Listen here:

A very "smart" Dutchman named Henkie smelled the potential of a Dutch cover-version of "Little Peter Rabbit".

He called it "Lief Klein Konijntje" and it was indeed a bestseller in 2006.

Nr 11 in the Dutch charts and Nr 1 in Belgian charts.

The credits don't mention it is an arrangement of "John Brown's Body" nor of "Little Peter Rabbit".

Listen here:

More versions here:

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten